JTF (just the facts): A total of 37 photographs/photographic objects displayed in the three rooms and the corridor of the gallery.

In the East Gallery are 4 multi-layered Duraclear prints, processed with water from the Flint River, Michigan and exhibited in LED Lightbox frames (3 of the 4 are roughly 89×49 inches; 1 is 20 x 14 inches.)

In the Viewing Room are 3 gelatin silver prints, developed with tap water from the Flint River, Michigan, supplemented with vitamin C, bleach, and red wine (8×10 inches) and 1 multi-layered Duraclear print (roughly 64×45 inches.)

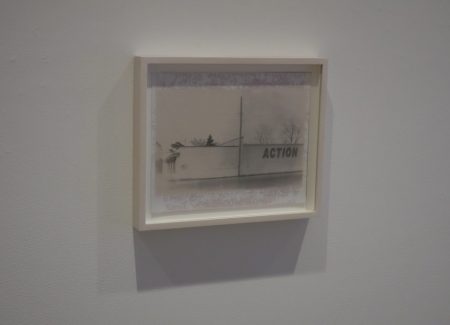

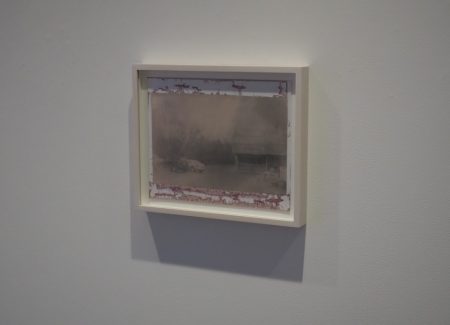

Wrapping around one wall in the corridor and into the West Gallery is a series of 24 gelatin silver prints developed with tap water from the Flint River, Michigan, supplemented with vitamin C, bleach, and red wine. Another gelatin silver print (8×10 inches) from the series is displayed in a recess along the wall.

In the West Gallery are 4 circular simulations of starry skies made from cocaine spread on black photographer’s cloths (60 1/8 inches in diameter.) All of the works are unique. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Recursion governs the thinking of numerous contemporary artists, usually as a layer of hidden meaning that undermines the surface appeal of their work by serving as a veiled political critique. Turner Prize-winner Simon Starling, a pioneer of conceptual circularity, is always seeking ways for subject and process to comment on each other. His Shedboatshed (2005) began as a simple wooden hut that he found, bought, disassembled, and turned into a boat, sailing it down the Rhine; at the end of his journey in Basel, he tore the planks apart and rebuilt them again as a hut, which he donated to a museum—a canny response to the ready-made in the age of ecological recycling and Transformer toys.

For One Ton II (2005) he photographed a South African platinum mine, making 5 platinum prints out of the material from the site. The title refers to the 2,000 lbs. of rock that must be refined in order to yield a smidgen of the precious metal. Tacita Dean’s film Kodak (2006), documenting the final days of a Kodak factory in France, was shot with Kodak film manufactured by the obsolescent plant. Vik Muniz and Lisa Oppenheim have slyly addressed concerns about pollution and waste by making images that embody in their construction what they illustrate.

It might be said that all of these artists are extending ideas and strategies proposed in the 1960s by Robert Smithson and others in the Earth Art movement; it could also be said that every photograph of the sun, moon or stars taken since the 1840s has been self-reflexive.

In this crowd, Matthew Brandt has emerged as perhaps the most zealous practitioner of recursion. Whether in works such as Dennis (2007), a baby picture on photographic paper coated with the mother’s breast milk; or in his Trees series (2009-2011), in which wood from a state park was pulped as the photographic paper or burned as ash for pigment; or Lakes and Reservoirs (2008-), processed with unfiltered water from various places in the photographs, he has found original techniques that more closely integrate the material world and the immateriality of representation. Coincidentally (or not), in an age when digital images are produced and deleted by the billions every day, his methods make his selection more personal, treasured and rare. Dennis can’t be dismissed as just another baby picture if the unique, bodily substance that has nourished the boy from birth is woven into the fabric of the object. In his La Brea tar pit series, extinct animal skeletons were depicted as if magically projected and darkened by smoke on against a cave wall, ideal objects for exposing the fossilizing process of photography.

For his third show at Yossi Milo, Brandt’s photographs fuse more topical subjects with modes of production, this time by bathing his prints in water from the Flint River in Michigan. This polluted stream, which was never supposed to be a source of drinking water only became so in 2014, when city officials diverted it into the homes of residents to cut costs. After the tap water was tested in 2015 and found to contain dangerously high levels of lead—without the largely poor and African-American population being informed of its toxicity—the federal government stepped in and began a criminal investigation. The Michigan governor, Rick Snyder, was forced to apologize and nearly impeached.

Brandt has made two bodies of work from these scandalous materials. One uses the Brutalist architecture of Flint’s dam and waterfall as the shadowy backdrop for abstract swirls and ribbons of color (cyan, yellow, purple, green, red, and pink.) A few of these pieces are displayed as glowing transparencies in light boxes. The other series more realistically portrays the many bridges that traverse the river. Printed as gelatin silver 8x10s, in ghostly shades of gray, the pictures are hung as a singletons or in a row of 24, their regimented uniform small size complementing the drabness of the subject.

Brandt’s color is cheery, like a psychedelic lollipop; his black-and-white is washy but elegant, similar in its faint, blurry outlines to Anselm Kiefer’s lead images or Marlene Dumas’s portraits. It can’t be forgotten in both cases, though, that Brandt is making art from the residue of an environmental disaster. The crippling effects of lead on the mental development of children is well-documented; what the high levels in Flint’s drinking water have done to people there won’t be known for decades.

Both series are designed to deliver the same sneaky jolt as Andres Serrano’s most notorious image. The crucified Christ, bathed in tones of ruby and gold, had a majesty until you learned it was photographed in a jar of urine. Oppenheim played similar tricks when her production notes for Smoke revealed that the billowy clouds, in what appears to be an homage to Stieglitz’s Equivalents, were actually noxious fumes from newspaper reports of an oil fire, a bombing raid, a volcano, or a riot.

All of these works are helpful in undermining the credulous acceptance of photography as automatically truthful, and in recalling the origins of the medium in industrial chemistry and metallurgy. Digital technology is hardly less environmentally neutral. (You don’t want to know what’s in your iPhone.)

By invoking an ongoing human disaster like the Flint water crisis to make art, however, a photographer should be clear about the purpose and the risks of being viewed as glibly opportunistic. Is Brandt demonstrating, as many artists have, that pollution and catastrophe can be deceptively beautiful? Or is he is commenting, more subtly, on the sinister specifics of lead in the water in Flint and the twisted representations that will ensue for its citizens? If so, the message is distorted and I suspect that framing it in ad-biz light boxes is not the optimal vehicle.

His tondos of cocaine on black velvet, the powder spread on the cloth to simulate photographs of the night sky, suffer from being too cute. Like Fred Tomaselli’s constellations of Xanax and LSD pills, they’re funny and kitschy, flattering movie stars and baby boomers by making jokes about their drug habits.

Brandt is of course aware that both the polluted waters of Flint and the cocaine trade have deadly consequences, but neither body of work expresses profound worries about those might be.

He has called the times when process and subject harmonize, and “real meets image,” as “kissing the mirror.” Whatever he was doing with his mirror in this show, it doesn’t reflect the same balance of vision that has thus far made his career so enjoyable and impressive to follow.

Collector’s POV: Prices range from $3500 for the single gelatin silver prints to $30000 for the Duraclear prints. The set of 24 silver gelatin prints is $45000. Each of the four circular works on photographer’s velvet is unique and $32000. Brandt’s work has just begun to enter the secondary markets in the past few years. Recent prices for the few lots that have changed hands have ranged between roughly $6000 and $9000.