JTF (just the facts): Published in 2017 by Abrams Books (here) to accompany the exhibition of the same name at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (October 18, 2016-February 26, 2017). Hardcover (6 x 7 ¼), 792 pages, with 580 color and black and white illustrations, $40. Includes a preface by Laurence Engel and essays by Robert M. Rubin and Marianne Le Galliard, along with an interview with Nicole Wisniak (by Rubin) and a selective chronology. (Cover and spread shots below.)

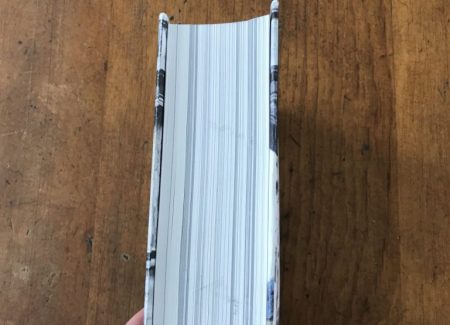

Comments/Context: The format of this catalog is as unconventional as many of the opinions in it. Unlike the glossy-stock, ceremonial tomes that typically arrive with photo exhibitions, including all of Richard Avedon’s previous ones, this is compact, thick, and printed largely on matte paper. Shaped like Laure Beaumont-Maillet’s 1993 brique of Atget’s photographs, it can be gripped easily in one hand, like a Larousse student encyclopedia.

Featuring unprecedented numbers of Avedon photographs, the contents are packed with alternate takes, contact sheets, magazine layouts, annotated prints, never-before-published portraits and documents (reviews, letters, drafts of letters.) Chapters are divided by piquant Avedon quotes, white words on black sheets: “I’m drawn to photographs in which the light is raw and the defenses are down. I find passport pictures beautiful.” The topics of the essays are equally offbeat, taking research in new directions: Avedon and the movies; his work for the Paris intellectual-celebrity magazine Egoïste; and his collaborative relationship with Jacques Henri Lartigue that resulted in the ambitious picture book Diary of a Century (1970).

The front cover is an Avedon photograph of Audrey Hepburn. Taken on the set of Funny Face (1957), the Paramount musical that was costumed in MGM’s lavish manner, it’s an image with a dual authorship, one fictional, the other real. The film was directed by Stanley Donen and starred 58-year old Fred Astaire as Dick Avery, a highly renowned and worldly New York fashion photographer based loosely on the career and personality of Avedon. The much younger Hepburn played a mousy bookseller named Jo Stockton, discovered by Avery in Greenwich Village and propelled to be the face for a publicity campaign for a New York fashion bible, Quality Magazine, and the mannequin for a Parisian couturier, Paul Duval.

In the photograph Avery/Avedon has posed Stockton/Hepburn off-center in front of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel in the Tuileries. The chic and stark architecture of her black dress and hat is outlined against the white sky and gray stone. Floating around her are shiny colored balloons (red, pink, blue, cyan, yellow, green), the strings held by her and a matronly vendeuse.

The balloon scene is the first in a sequence of seven in the movie that switch between live action and freeze-frames. As Avery/Avedon photographs Stockton/Hepburn in various places around Paris, dressing her to impersonate everyone from a tearful Anna Karenina at the railroad station to a virginal bride in white chiffon at a country church, the movie pauses for a moment on the pose that the photographer has coaxed from his model. The still image then undergoes tone reversals and color separations, Hepburn/Stockton becoming less identifiable until in some cases nothing is left but a layered series of faceless printing plates.

Robert M. Rubin sees these deconstructions as revolutionary. In the exhibition, the film clips and freeze-frames were arranged in a semi-circle of niches around the edges of the opening room of the BNF show, with a photo-booth and a movie camera in the center. In the catalog, which has a negative of the front cover image on the back cover, he calls the sequence “a key moment in cinema and photography…unlike anything that Hollywood had ever seen.”

He is careful not to depreciate Donen who, after all, had five years earlier—and more wittily—exposed the conventions of set and sound design, and the artifice of cinema in general, when he directed Singin’ in the Rain. But to further his grander revision of Avedon as a postmodernist avant la lettre, Rubin needs to emphasize both the photographer’s directorial role in the film and the novelty of these images. Avedon was credited as “Special Visual Consultant.” He almost certainly designed the freeze-frames and was solely in charge of the more elegant and less disruptive opening titles.

The innovative techniques of photography in Funny Face were recognized at the time of its release with a special citation from the National Board of Review in New York. Rubin also reprints an excerpt from a 1957 review in a Paris magazine by French director Eric Rohmer, who singled out the moving-to-still image sequence as “delightful, even if the rest <of the film> isn’t really satisfying…. A click and the screen freezes, and the realism of the film gives way to the sophistication inherent in photography….I have sometimes argued vehemently against the plastic tendencies of certain filmmakers who, imagining they are copying the old or the modern masters, are barely creating images worthy of calendars. Here, on the contrary, the effects relate to a technique that feels like pure photo-graphy, without any pictorial reference. Indisputable proof that color, far from subduing the art of the image, opens up new enthralling horizons.”

Rubin’s essay cites other reviews that noted the film’s unusual treatment of color, first in a scene when Astaire photographs Hepburn under a red safety light in a darkroom and then in a later scene set in a smoky beatnik basement boîte.

I admit that the film had never impressed me as artistically daring, and Rubin’s advocacy forced me to rethink my dismissive attitude. Viewing any visual in a big-budget Hollywood musical as “avant-garde,” though, takes some adjustments, and his argument for the historic importance of the live-action-to-freeze-frame sequence would be stronger if he could name directors or cinematographers—or other film historians—who later cited it a “key moment in cinema.”

He doesn’t. Or can’t. Instead, he doubles down on the hyperbole and makes other provocative statements about the use of color in the film. “Is it a stretch to consider Funny Face a necessary precursor to Antonioni’s Red Desert (1964)?” asks Rubin. From the evidence he has marshaled, I would have to answer, reluctantly, “yes, it is a stretch.” Rohmer’s enthusiasm may have been an isolated case.

Of course, just because Rubin doesn’t have a supportive quote from Antonioni doesn’t mean that he is wrong about the experimental spirit of Funny Face having an impact on other filmmakers. Avedon own words throughout the text reveal a deep and easy familiarity with film technique: “I lit each restaurant, each street as if I were lighting a movie.” The 8×10 camera “has a very shallow depth of field, which means you can throw the background out of focus, reducing the sum of detail and creating an ambiguous narrative relation between the knowable (what’s sharp) and the unknowable (what’s blurred), which is what Rene Clair does, with gauze, in Le Million.”

Is it too obvious to mention the film’s possible influence on perhaps the most famous freeze-frame—and zoom—in cinema history: the last shot of Antoine Doinel on the beach in Quatre Cent Coups, released only two years after? The essay doesn’t mention Truffaut nor the example in Avedon’s oeuvre that most closely uses color tone-reversals similar to the ones in Funny Face: the portraits of the four Beatles for the White Album.

The 2001 exhibition and slim catalog, Made in France, was devoted to Avedon’s fashion photography, which may explain why this phase of his long relationship with Paris isn’t more extensively surveyed here. Avedon’s France also has a bias toward process rather than finished masterworks. There are as many as a dozen small photos reproductions per page and the BNF exhibition featured numerous vitrines full of contact sheets. Such an approach to archival material, however instructive, doesn’t encourage an appreciation of these exquisite pictures.

Some of Rubin’s generalities (“French culture underpins virtually all of Avedon’s art”) seem pitched toward his sponsors rather than buttressed by the record. While French philosophers, novelists, painters, and directors, before and after WWII, had a decisive impact on New York’s intellectual class, of which Avedon was a member, it’s hard to think of a French photographer who shaped his flamboyant style, either in fashion or in portraiture. (Nadar’s influence on Penn is easier to see than it is on Avedon.)

One of his mentors, Alexey Brodovitch, was at heart an aristocratic Russian; the other, his contemporary Marvin Israel, was as much a product of Jewish New York as Avedon. His self-proclaimed affinity with Proust needs more than his own testimony to be convincing. Rubin notes that his library contained three complete sets of A la recherche du temps perdu. I’m skeptical that anyone so frantically busy, day and night, had the time or patience to finish even one volume. My guess is he memorized a few quotes and repeated them to dazzle interviewers.

I expect Rubin might agree that Avedon probably never finished Proust—he finds only one penciled annotation in the books: the word “asparagus”—and one of the strength of the catalog is its candor. (Credit is due to the Richard Avedon Foundation for giving Rubin such a long leash.) The essay is respectful of Avedon’s crackling energy and intelligence but honest about his insecurities, in particular his gnawing disappointment that the New York curatorial establishment never fully accepted him as anything but a rich, talented commercial artist. Rubin believes that Avedon was never forgiven for boasting in a 1958 New Yorker profile that he was making almost as much money as Picasso. Another crippling blow came from a brutal (and obtuse) take-down of the book Nothing Personal in 1964 by theatre director and critic Robert Brustein in The New York Review of Books. Avedon was so wounded he didn’t make another portrait of an artist for three years.

Rubin argues that Avedon rescued himself from profound despair by immersing himself in the work of Lartigue, whose work he had fallen in love after John Szarkowski exhibited it at MoMA in 1963. It became Avedon’s mission to make the sophisticated boy wonder as famous in France as he was becoming in the U.S. and to present the work as a kaleidescope of memory and image. He devoted years to the project, the effort culminating in Diary of a Century. A slide-show in the last room of the exhibition flashed the lovely melange of photos and documents that the two men constructed together over many edits on cross-Atlantic visits.

Marianne Le Galliard’s essay is equally frank about Lartigue, who was shockingly obscure in Paris photo circles until late middle-age. Cartier-Bresson, it seems, had never met him! Despite a feature in Life and the MoMA show, the French art critics failed to appreciate his native genius until Diary of a Century. As this exhibition proves, Avedon had everything to do with that.

Both Lartigue and Avedon edited their own work differently as a result of their collaboration, which makes the sharp break in their friendship even harder to understand. According to Le Galliard, Avedon blamed Lartigue for the French publisher’s leaving his name off the French edition of the book, even though it was a typographic goof and corrected with an erratum.

The incident may have exposed deeper, hidden problems. Did Avedon suspect that Lartigue was insufficiently grateful for the years he was sacrificing, editing another’s work rather than creating his own—and this omission was the tipping point? Or was Lartigue eclipsing him in critical favor? The French publisher may have left off Avedon’s and Bea Feitler’s names because it was “bad for business” in France, as Rubin suggests, and also out of national pride: they didn’t care to promote a pair of Americans for elevating a French artist they should have lauded many years before.

Le Galliard is on shakier ground when she repeats the idea that Szarkowski distorted Lartigue to fit his master plan for photography at MoMA. (This is also the dubious thesis of Kevin Moore’s book The Invention of Lartigue.) She writes that Szarkowski converted the boy photographer into “an amateur genius who never intended to make art—and thus a forerunner of the modernist tradition exemplified by Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander.”

This is wrong on several counts. It’s absurd to think that a curator, new to the job, would have go over-the-moon crazy for photos by a 10 year-old amateur in order to prepare the way for the archly self-aware Winogrand or Friedlander, whose work he didn’t then even know. Szarkowski was never a soigné Modernist, at least not in the way that Alfred Barr or Walker Evans were. He never spoke a foreign language with any confidence and didn’t visit Europe until, I believe, 1963. He was a Midwestern American with homegrown brilliance and a background as a working photographer, not an art historian. I doubt he ever read Clement Greenberg or was impressed, if he did.

What made him an exceptional curator, whose approval Avedon craved, is that he didn’t begin his tenure with any program in mind other than a wish to highlight individual photographers and identify the qualities that made their talent vital—something he thought Steichen hadn’t done enough. Only slowly and sporadically did the museum build upon Newhall’s idea of a tradition and create a broad line of “documentary” artist photographers through Atget and Evans. His enthusiasm for Lartigue was a response to the spontaneity of the pictures, to the social world that Lartigue captured so effortlessly, from the inside.

According to Rubin and Le Galliard, Avedon saw more clearly the staged artifice that went into the childhood pictures. What Szarkowski regarded as instinctual improvisation, a boy posing his servants for his own amusement, Avedon viewed as a constructed performance.

Rubin is determined here, and elsewhere, to do some “inventing” of his own, twisting Avedon to fit into a mold that would allow him to be the forerunner of his friend Richard Prince. As he said in a recent interview, “I see Avedon as a postmodernist who wanted to be recognized as a high modernist, to be in the canon of the great artists he grew up worshipping. But he was not able to take that final step to postmodernism. He was arguing, correctly, that photography, all photographic images, are constructed images, in opposition to the idea of the decisive moment of Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Garry Winogrand’s street photography, which had more currency in highbrow circles. If Avedon really went to the end of his thinking, he would have embraced the ‘pictures generation’…. He just couldn’t make the next step, which is to say, if photography is only constructed moments, why can’t they just be fake? He was still stuck at the level of constructing photographic moments when Cindy Sherman and Richard Prince came along. Prince’s thing was “I’m only going to take photographs of photographs.” Cindy’s thing was to make film stills for films that never existed. Everybody had their own angle on ‘pictures.’ Some of Avedon’s photo-narratives come close to that but aren’t that. He couldn’t, because he was a photographer with a mission to elevate his craft to the level of art. Prince could, because he wasn’t really a photographer in the first place.”

The evidence that Rubin gathers for this argument doesn’t make a lot of sense. Postmodernism is as much a smart-ass attitude, a punkish disrespect toward the sacerdotal worship of Modernism, as it is any one procedure for making a picture. The collaged photographs of a wealthy Venice costumed ball that Avedon cooked up in the darkroom in 1992—a series published in Egoïste as “Le Bal Volpi”—seem to be a response to Winogrand’s and Larry Fink’s party shots, or maybe the expressionism of James Ensor and George Grosz. They’re worlds apart from the deadpan irony of the Pictures Generation.

If Avedon had opted for postmodernism, he didn’t need Richard Prince to show him the way. He had Andy Warhol constructing images by the truckload in his Factory only a couple of miles away.

That he never imitated Warhol’s cynicism, except in the competitive desire to make piles of money, says a lot about his earnest ambitions for himself as an artist. He came of age when educated New York and Paris talk was dominated by Existentialism and Psychoanalysis. Despite his professed belief in surfaces, Avedon had a respect for intellectual substance as well as performance; he wanted his photographs to reveal people’s troubled souls, as his friend Arbus could do with stunning regularity. Richard Prince harbors no such illusions about photography.

My demurrals notwithstanding, Avedon’s France deserves to be reckoned with. Rubin thinks for himself and researches questions diligently. Received opinion won’t do for him. His is not a book I will be putting away on a high shelf. It is more like Diary of a Century than living room décor. I expect to be returning to it, if only to argue with him, for many years.

Collector’s POV: Richard Avedon is represented by Gagosian Gallery in New York (here) and Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco (here). Avedon’s work is routinely available in the secondary markets, as many of his most famous images were made in editions and portfolios of 50, 75, 100, and even 200 prints. The artist’s fashion images and portraits are relatively equal in price at this point, with the iconic images generally finding buyers in six figures, and most other images priced in five figures. The white glove Avedon sale at Christie’s Paris in 2010 (detailed results here) is probably the best proxy for the current market. In that auction, a print of Dovima with elephants, Evening dress by Dior, Cirque D’Hiver, Paris, August 1955, 1955/1978, set a new auction record for Avedon at €841000 (just over $1100000).